Ashraf Rushdy in The Conversation: The Art of the Public Apology

Wesleyan faculty frequently publish articles based on their scholarship in The Conversation US, a nonprofit news organization with the tagline, “Academic rigor, journalistic flair.” Amid a flood of accusations against public figures for sexual misconduct and other improprieties, Ashraf Rushdy, the Benjamin Waite Professor of the English Language, writes a piece exploring “the art of the public apology.” Rushdy is also professor of English, professor of African American studies, and professor of feminist, gender and sexuality studies. Read his bio in The Conversation.

The art of the public apology

Ashraf Rushdy, Wesleyan University

Just prior to his sentencing, former USA Gymnastics physician Larry Nassar formally apologized to the more than 160 women whom he’d sexually abused. He joins a growing list. Over the past few months, many public personalities accused of sexual assault have apologized in public.

Many of us at this point are wondering what these apologies mean. Indeed, like others before him, Nassar said that an adequate apology was impossible. He stated,

“There are no words that can describe the depth and breadth of how sorry I am for what has occurred. An acceptable apology to all of you is impossible to write and convey.”

What, then, is it that he and other public figures are doing when they say sorry publicly?

In a forthcoming book, I look at different kinds of public apologies, including the kind of celebrity apologies we’ve witnessed in the past few months. What I argue is that public apologies are a type of performance and therefore should be understood as being different from private.

What is a public apology?

Televised public celebrity apologies, watched by millions, are a relatively recent phenomenon.

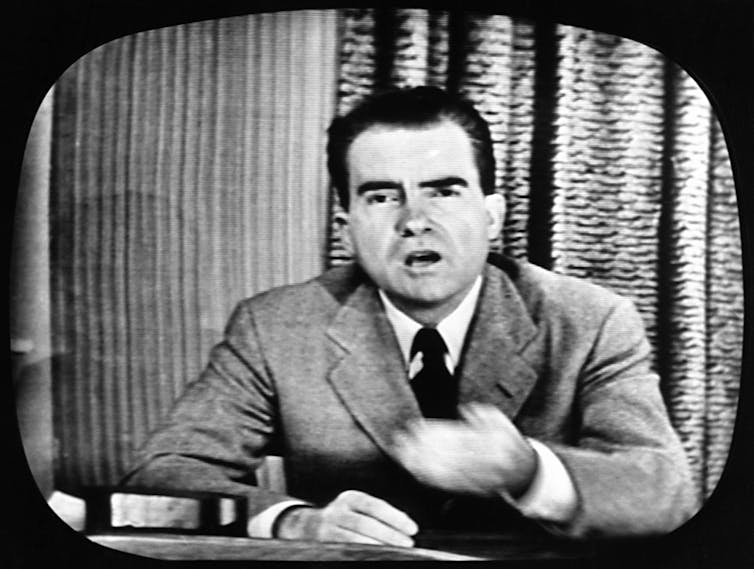

In his 1952 “Checkers speech,” televised live to an American public, Richard Nixon, then Republican candidate for vice president of the United States, defended himself against charges of financial impropriety. Nixon did not explicitly apologize, but as journalist Caryn James noted, the speech began by “sounding apologetic.”

In 1998, in a televised address to the American public, Bill Clinton apologized for his affair with White House intern Monica Lewinsky. Clinton expressed regret but denied responsibility. The apology failed. In a CNN poll taken immediately after, 60 percent of those polled said that Clinton should have explicitly used the words “I’m sorry.”

Less than a month later, at the White House prayer breakfast, Clinton revised the apology. This time Clinton used the language Americans wanted—“I am sorry”—and the biblical terms with which they were familiar—“I have sinned.”

Scholar of public apologies Edwin Battistella noted in his book Sorry About That how this was a successful apology. Indeed, this time more people believed they were witnessing sincerity.

And that is the point of a public apology. It can provide public personalities an opportunity to regain public approval.

The purpose of a public apology

I would argue that these celebrity apologies are not much different from those offered over criminal violations in court. They are all driven by an ulterior motive.

Take, for example, the case of corporations. As philosopher Nick Smith discusses in his book Justice through Apologies, they do so to limit their legal liability. Similarly, philosopher Jeffrie Murphy explains what it means for someone to apologize to the court when a reduction in their sentences is at stake. Nassar’s apology, offered just prior to his sentencing, was a combination of celebrity and court apology.

Apologies, in other words, try to control the damage.

In today’s consumerist society, the public is God. And so the celebrities apologize to us—the public—in a way that people earlier used to appeal to their God. In 1697, for instance, Judge Samuel Sewall went to South Church in Boston to apologize for his role in the Salem witch trials, in which 20 innocent people were executed in a fit of mass hysteria. He asked his fellow congregants for their “pardon,” but his appeal was primarily that “God, who has an unlimited authority, would pardon” that sin, and all his other ones.

The public apology today is an act of publicity. Many of the public personalities are appealing to their audience not to boycott their product, which, in other words, is the celebrity.

Private vs. public

Private apologies are different.

More often than not, we can assess when someone is sincere by witnessing what she or he does after apologizing. We can see if those who apologize to us have indeed reformed their behavior. We are not in a position to see that in the case of celebrity apologies.

A private apology is generally not a performance. Our friends and lovers apologize to us in private to an audience of one, or few. And they are generally not professional performers. Celebrities and other public personalities are apologizing to an audience of millions.

Private apologies are heard, while public apologies are meant to be overheard.

Why an apology matters

Nonetheless, apologies matter in public life, just as they do in private. The important thing about all forms of apologies is that they reveal and alert us to the limits of what is acceptable.

In our personal lives, a person who repeatedly apologizes for the same act or for acts of the same type is revealing the deeper problem behind that behavior (anger, for instance, or disrespect). The victim forgives, if she does, on the understanding that the behavior is unacceptable.

This recent wave of public apologies reveal the outrage against crimes against women and that support from powerful institutions for that behavior is no longer acceptable.

Finally, apologies alert us to their own limits. In our private lives, we recognize that the words “I am sorry” are meaningless without a change in behavior.

Ashraf Rushdy, Benjamin Waite Professor of the English Language, Wesleyan University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.