Students from Wesleyan, Belarus, Russia Discuss Crisis in Ukraine

Calling the attacks in Ukraine “a war” is against the law in Russia, and all media organizations there must use the term “special military operation (SMO).”

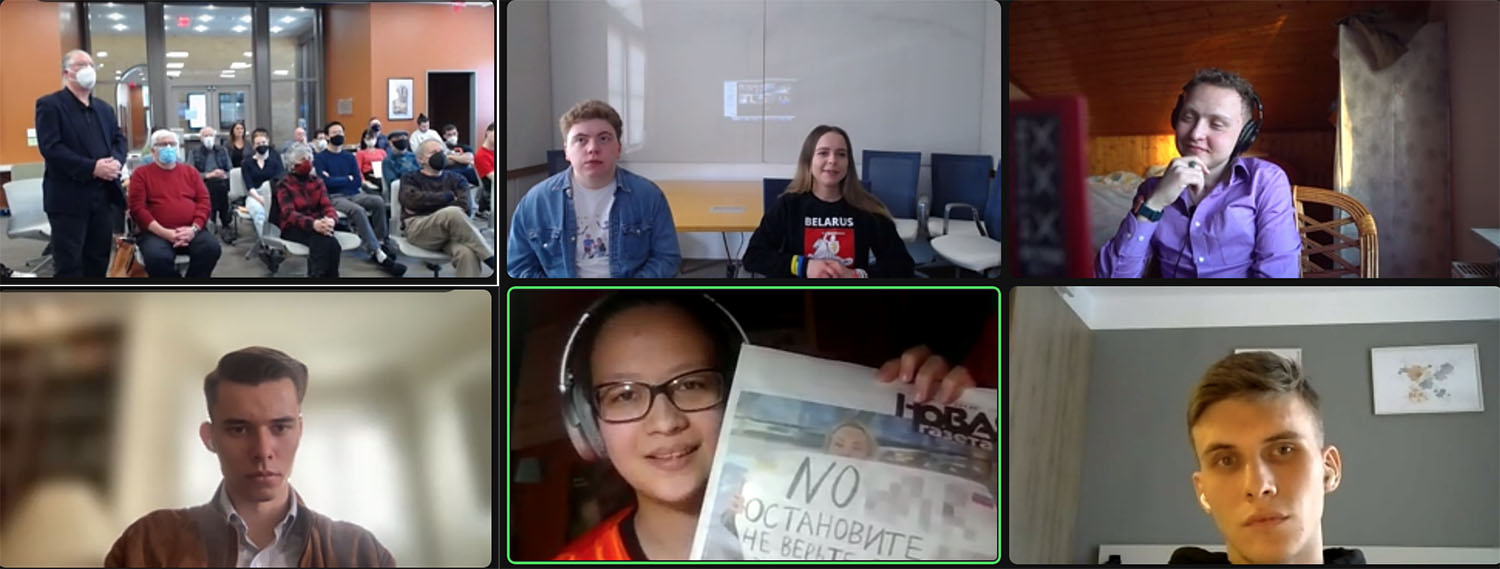

“If anybody with a newspaper [doesn’t use SMO], next day, you’re in in jail,” said activist Frantsuaza Li of Moscow during Wesleyan’s fourth Ukraine-Russia Crisis: Livestream Conversations series event on March 25. “Russian propaganda works. Not because Russian people are devils, and they think that [the war] is a good thing. Because there [is] no information in the internet. The government blocked many newspapers. The government blocked Facebook, YouTube, and people . . . can’t find the truth.”

Li, a sophomore at Higher School for Economics University in Moscow, joined the panel just hours after being convicted in a trial for demonstrating on behalf of Ukraine. Her punishment is to pay a fine.

She explained that she’s against the war, as are many Russian citizens. “There are [many who] are very ashamed of this,” she said. “I want the international community to know that we didn’t want this. It’s very dangerous to protest now, but we do all we could do.”

The Livestream Conversation with Ukraine series was developed by Barry Chernoff, director of the College of the Environment and Robert Schumann Professor of Environmental Studies, together with Katja Kolcio, associate professor of dance and director of the Allbritton Center, in an effort to humanize the war in Ukraine by hearing perspectives from students, journalists, and civic leaders in or from the war zone. Chernoff and Kolcio have developed working relationships with scholars and civic leaders in Ukraine since 2017 in environmental studies.

“We appreciate the fact that our panelists are taking the time and risking their safety to be here with us,” she said.

Li was joined by fellow panelists Tim White ’23, a film major from Moscow; Lera Svirydzenka ’25, a political refugee from Belarus; Alexander Slavin, an independent media journalist in Russia; and Nikita Vushau, a recent graduate of Belarusian State University.

Journalist Slavin recently fled his native country and is now residing in Serbia. “As a journalist, there is really no way to write from inside the country right now. After new rules, after new laws, you really can’t afford to have some sort of freedom of speech right now in Russia. For me, it’s a necessity. I need words. I need my journalism.”

Unlike Li, Slavin feels the Russian state propaganda is weakening as more and more people begin to “wake up” and learn that the “special operation” isn’t just to free Ukraine from fascism.

“Right now, they try to make us believe that there are a lot of people who are supporting this ‘special operation,’ and of course there are people who support [Putin]. There are a lot of people who are influenced . . . by this propaganda and this narrative.”

Western media, he suggests, could help change the narrative by differentiating between the people and the government. “It’s all Ukraine versus Russia,” Slavin said. “As I understand it, our government in Russia [is] making our people suffer. They are really repressing them. They are making the economy worse. They are going into the total bankruptcy of the country, and in my perspective we need to call it Putin’s War against Russia and Ukraine.”

Bahdanovich, who was living in exile in Lithuania before continuing his education at Harvard, suggested the media treat Belarus in a similar manner. “There’s the new ‘real Belarus’ and then there’s the ‘Belorussia,’” he said, that has Alexander Lukashenko as president. Belorussia is “bogged down in the past, which is using barbed wire and batons to beat any freedom out of the people. This is the country participating in the war. Those are the aggressors and the right.”

Svirydzenka agreed. Since 2020, she’s and her fellow Belarusians have learned how to use alternative media, but Russians, she said, find this more difficult. And sanctions put on Russia make their fight against the war harder.

“The monetization stop on YouTube for Russian bloggers prevents them from spreading awareness and real information about the war as no one other than pro-Kremlin journalists has access to TV,” she said. “And the academic community—conferences are canceled— and many students cannot participate and their professors do not support them because ‘you are Russians.’ But this is actually not helping us to stop the war, it just prevents people who are trying to tell Russians, Belarusians, and the whole world about all the horrors happening from doing that. They are oppressed by their government, they are oppressed by the international community—they are oppressed by everyone and simply do not have space in this world to do something they were trying to do to stop the war. It all comes from seeing the difference between Belarus and Belorussia, Russian democratic society and the Kremlin.”

She went on to say that “we need to support people who are fighting against the war and not prevent them from doing that, because they simply do not have any opportunities. It makes all the democratic movements even harder, even though it was super hard before that.”

Film studies major White, who is interested in music, art, and Russian history and politics, lived in Moscow since the age of 2. Since 2014, when Russia invaded and annexed the Crimean Peninsula from Ukraine, White has “avoided state-sponsored media like the plague.”

He tends to read non–state-sponsored media through a virtual private network (VPN), a technology that encrypts internet traffic to shield online data from third parties. “About a week ago I was on the phone with my mother and I showed her how to turn on the VPN, and she was exhilarated to get to see Facebook again,” White said.

Vushau, who graduated from Belarusian State University last spring, participated and organized different political events in order to fight for free and fair elections. He moved to Poland the first day of the war. “I was living in a country that is just for terrible terror,” he said.

The panel provided Vushau his first chance to speak publicly.

“I don’t have the opportunity to share my thoughts [or] to do something . . . and this was killing me. So if I leave the country then I have the opportunity to do something right here. It’s important to volunteer to help Ukrainians.”

The ongoing Ukraine-Russia Crisis: Livestream Conversations series is hosted at the Fries Center for Global Studies. Co-sponsors of the event included the College of the Environment, the Fries Center for Global Studies, the Allbritton Center, and the Russian, East European and Eurasian Studies Program. Recordings of the three events are available online.

Frantsuaza Li suggested the international community explore the following organizations: OVD-info, the largest human rights organization in Russia; Doxa, a student media outlet whose editors have been prosecuted by the government for more than a year; SOTA, Zona.Media, and Meduza, independent media; Open Space (Открытое Пространство), the human rights project that supported activists; Roscomsvoboda, the Antimilitary Feminist Opposition.