Open-Ended Questions: New Exhibit at the Zilkha Gallery

Every exhibition presented in the Ezra and Cecile Zilkha Gallery establishes an idea–or an argument–of what art is, how art is made, who makes art, and what art does.

“With every presentation, we attempt not to narrow the answers to any of those big questions,” said Associate Director of Visual Arts and Adjunct Instructor in Art Benjamin Chaffee ’00. “We think critically about the art that is shown and also how we’re framing it.”

The most recent exhibition at Zilkha has created an interesting opportunity for juxtaposition. “Liquid Gold” includes a video installation and a sculpture by Assistant Professor of Art and Luther Gregg Sullivan Fellow in Art Ilana Harris-Babou. “seeing is forgetting and remembering and forgetting again” features works at the intersection of drawing, painting, photography, and sculpture by Carrie Yamaoka ’79. Both are on display through Sunday, March 5, 2023.

During the 2021-2022 season, the gallery staff had returned to explore the idea of showing multiple complementary solo exhibitions across the North Gallery and Main Gallery at the same time.

“With two concurrent and independent solo exhibitions, we work with each artist to develop their exhibitions on their own terms,” said Chaffee. “We can leave open the connections between them, allowing viewers to appreciate their differences or discover their similarities.”

Several of Yamaoka’s works address the notion of returning to something in the past and reconfiguring it. “I was also thinking a lot about time and memory and the passage of time,” said Yamaoka, which dovetailed with another concern of hers since 2016, which has been going back to older works and destroying them in order to create a new work.

When Chaffee offered Yamaoka an opportunity to display at Zilkha, she wanted to take the opportunity to think about the show differently, and have it be responsive to the site. “I realized coming back here many years later that, in fact, this is a tough place to install art in, in some ways, because the building itself is an artwork,” said Yamaoka. “It’s almost like it’s a sculpture of its own.”

Yamaoka viewed the gallery as a space analogous to a studio, and started thinking about working with photography–a return to a form that she was engaged with before she came to Wesleyan in the fall of 1975. She made a number of visits to campus in the summer of 2022 to take photographs of the space.

“I was interested in all the weirdness of the space,” said Yamaoka, who remembered her senior thesis show in 1979 when she displayed her drawings that explored the idea of erasure. Her work on that project under Jacqueline Gourevitch, as well as her undergraduate drawing classes with David Schorr, formed a basis for a lot of the way that she has proceeded to operate since then. “I think I’m a lot more rebellious now than I was then…Now I’m interested in subverting the structure that has been received,” said Yamaoka.

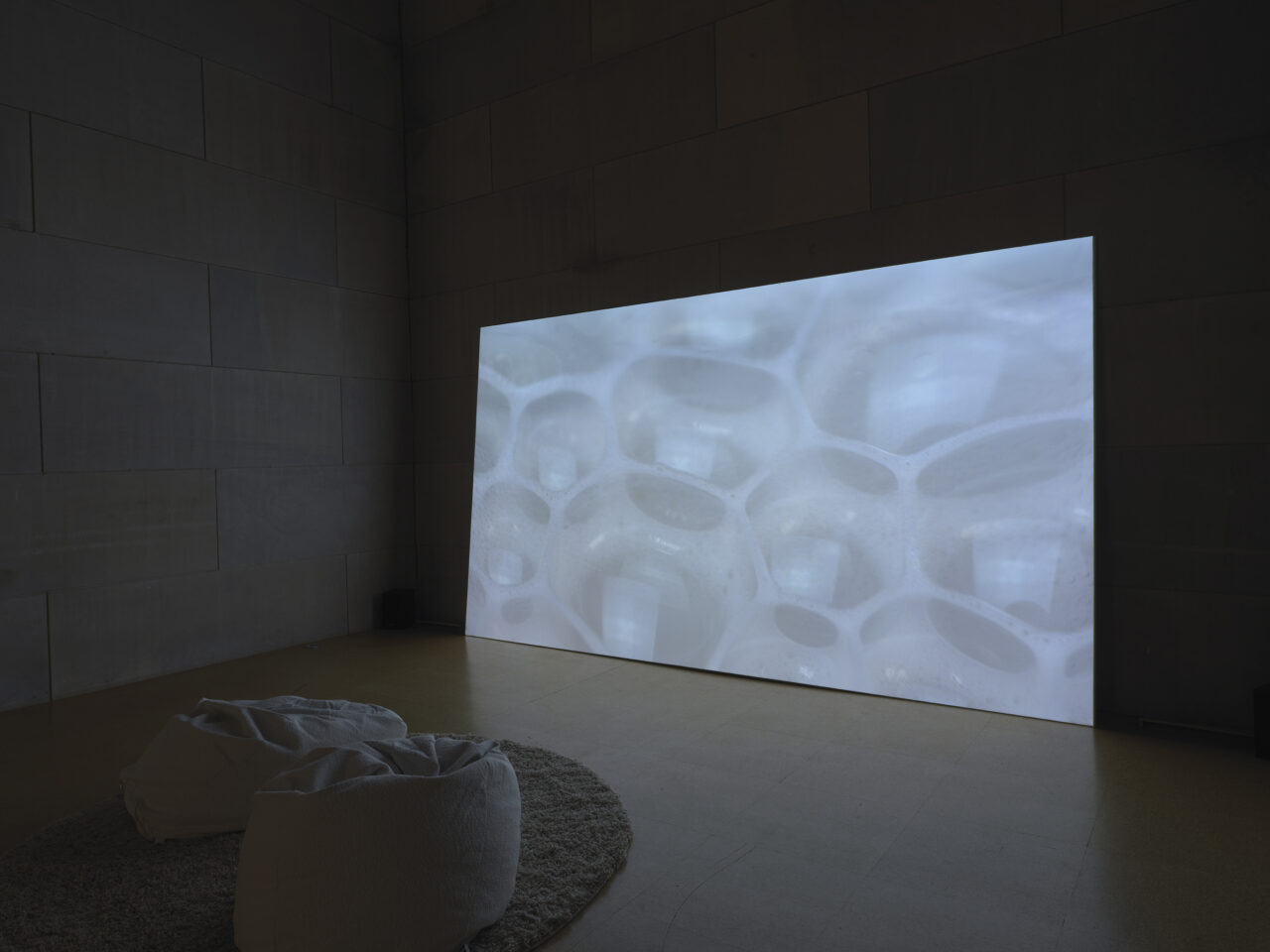

Harris-Babou thought the new exhibition was a great opportunity to share her research and process around a new series of works in progress that she had been commissioned to create for the group show “Milk” at the Wellcome Collection in London from March through September 2023. Her current piece is about Black maternal breastfeeding, as well as intimacy, closeness, and how trauma and joy are passed down through the body.

“This process has been one of trying out new sculptural techniques, things that I never would have been able to do before or couldn’t have done in another space,” Harris-Babou said.

Harris-Babou works in ceramics and video, experimenting with the two in her studio. She often will be working on a body of sculpture while she’s working on a video, and they evolve simultaneously. “I feel like so many of my ideas are expressed non-verbally through the objects,” said Harris-Babou. “A lot of the language and other references that exist in my mind can come out in the video where I can synthesize imagery and text and sound.”

Harris-Babou is teaching introductory and intermediate courses in time-based media this semester. She’s attempting to look beyond the context of contemporary art into vernacular video. “I really like to think about video in an expansive field,” said Harris-Babou. “We’re sort of living and swimming in video at all times in the internet age,” she said of the different references that come into her work, from the music she’s listening to, to the YouTube videos she watches. “I want to have students feel empowered to also bring the sort of ephemera and moving images from their everyday life into the classroom.”

The curatorial process for this spring started four years ago with research into potential artists, which included reading, attending lectures, and viewing other exhibitions. Chaffee and Exhibitions Manager Rosemary Lennox think about how to build a narrative between recent exhibitions in the gallery, as well as how an exhibition at Wesleyan would read in conversation with other presentations and contextualizations of the artists, both nationally and internationally. Their curation is also guided by feedback from conversations with the Zilkha committee, which is comprised of faculty from across the University–from Sociology to Anthropology–as well as student interns.

Before they make the decision to approach an artist, they do research, read what has been written about the work, how the artists describe it, and how past presentations framed the artist’s practice. All this information is important in articulating why it would be compelling to show their work in the context of the University.

“When we are speaking with an artist about exhibiting in the gallery at Wesleyan, we approach that conversation with some ideas of why a presentation of their work would be meaningful in the gallery now, but we also stay open to what might be relevant, interesting, and compelling for an artist within their practice,” said Chaffee. “When we can work together to make an exhibition that is generative for all parties, then the result is often more impactful for the audience as well.”

Both exhibitions are contingent on the viewer’s experience. Both artists are intrigued by the relational dynamic between the viewer and the object–what the visitor to the gallery makes from what they see.

“I think each work of art always really becomes complete when it comes into contact with the viewer…And so it becomes a different work with each new viewer who sort of completes it and brings along with them all of their histories,” said Harris-Babou, whose work incorporates the experiences and memories of several generations of her family through audio recordings.

“I’m starting to feel like I’m really interested in things that are not finished, that are still open-ended…that they’re still open to change, or open to revision, or open to modification,” Yamaoka said.

The result, with two very different artists existing alongside each other, is tremendously compelling. “It seems to be quite successful,” Lennox said. “It creates an opportunity to imbue the gallery with the potential for an aesthetic experience between the two exhibitions. I think that really helps broaden the appeal and allows the gallery to become a site of fluidity and creative risk-taking in the way we think about programming.”