Students Catalog Wesleyan’s Lost Fossil Collections

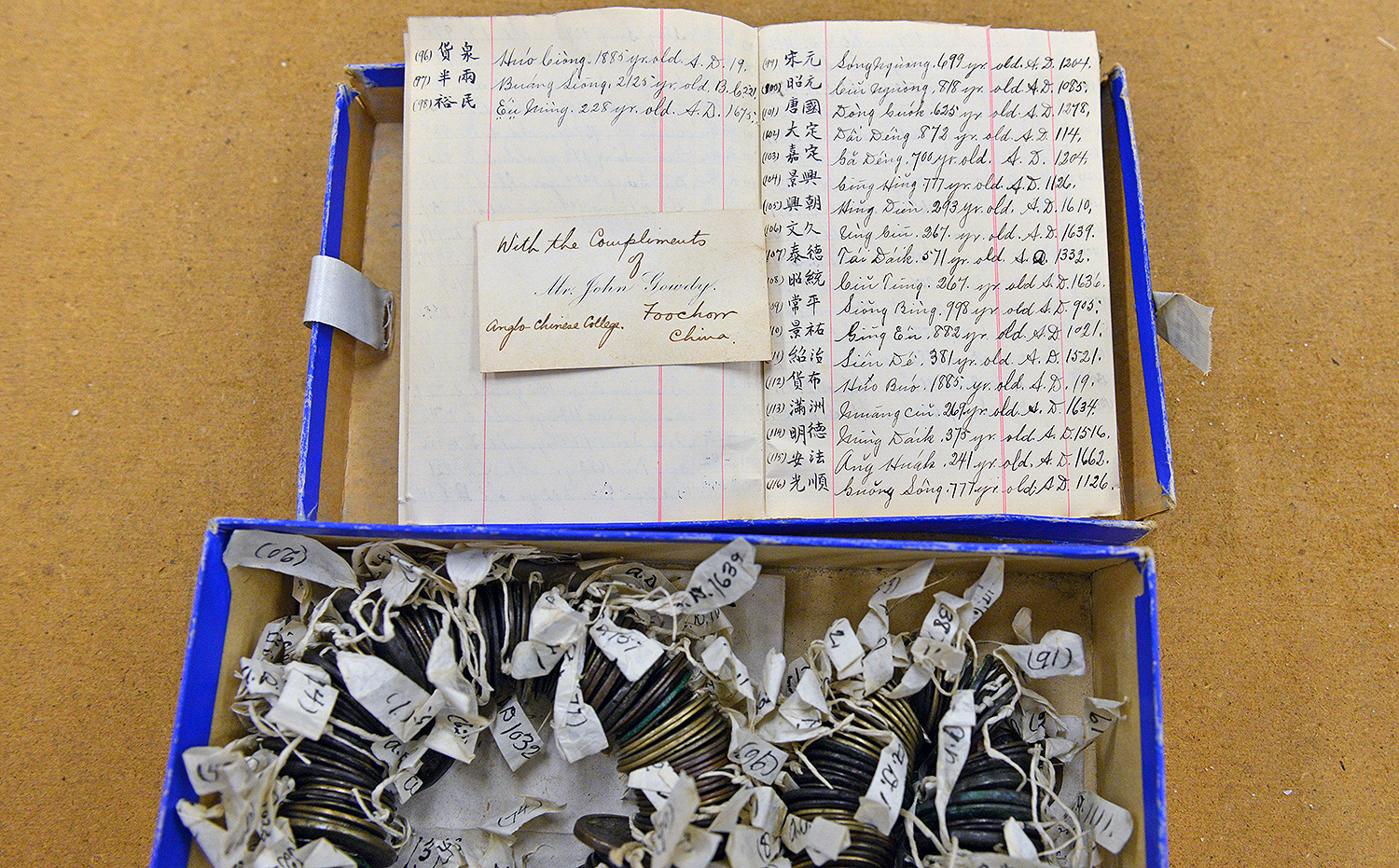

Scattered throughout campus are remnants of not only Wesleyan’s history, but world history. After the closing of the Wesleyan Museum in 1957, thousands of specimens in many collections were displaced, often haphazardly, to nooks, crannies, tunnels, attics, storage rooms, and random cabinets at Exley Science Center, Judd Hall, and the Butterfield and Foss Hill residence complexes.

Many of these specimens haven’t been accessed in 60 years.

“Sadly, few people are aware that Wesleyan has these unique resources,” said Ellen Thomas, the University Professor in the College of Integrative Sciences and research professor of earth and environmental sciences. “The collections have not been well curated, and not much used in education and outreach. We are discovering beautiful fossils, but the knowledge that they are at Wesleyan has long been lost.”

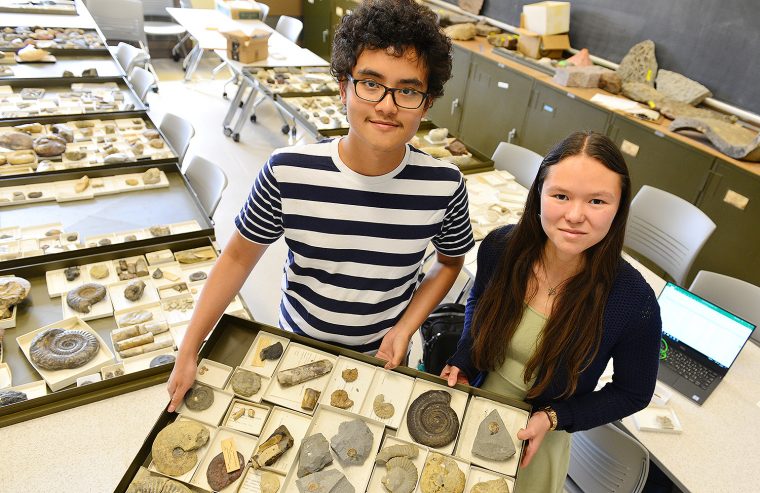

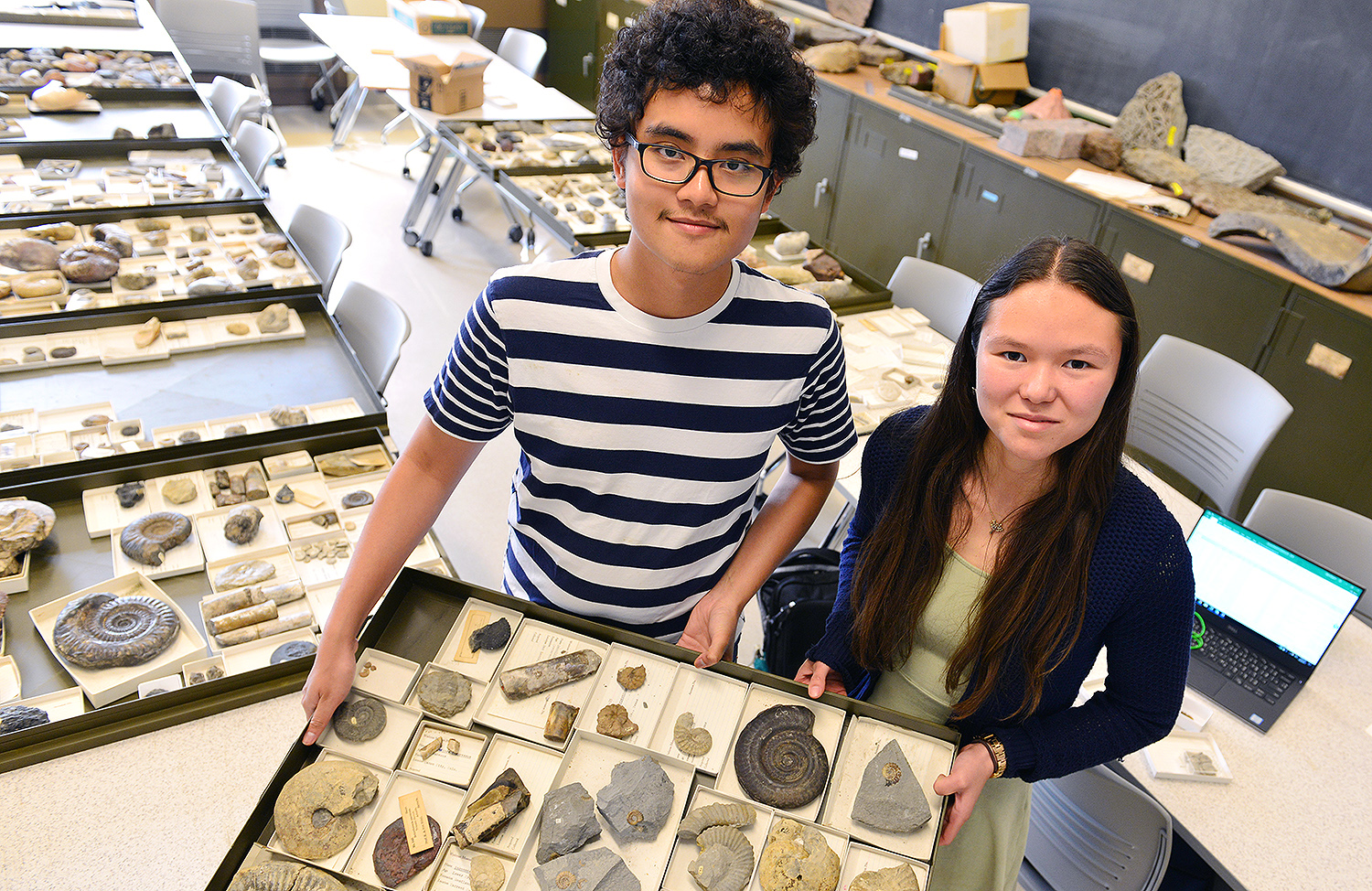

This summer, Thomas, along with two student research fellows, began the painstaking process of not only locating and organizing collections, but digitally cataloging their finds.

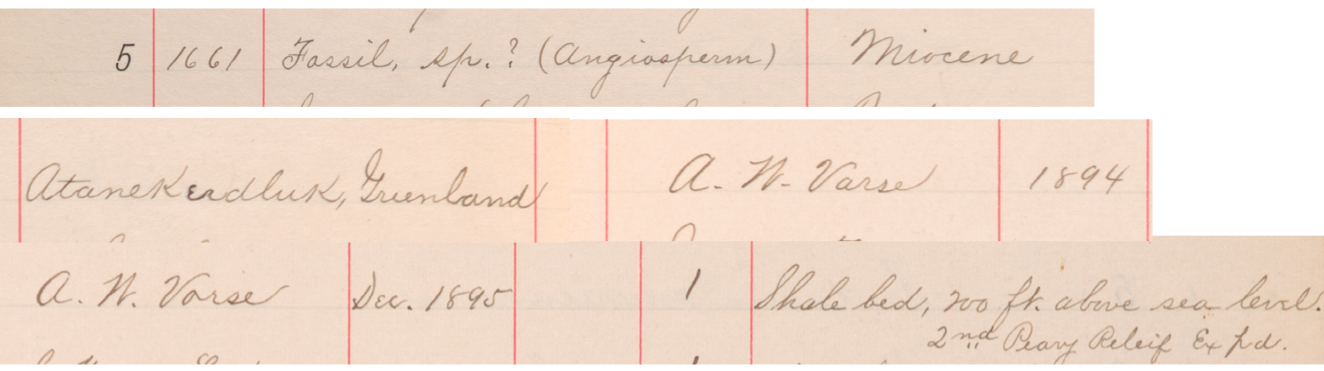

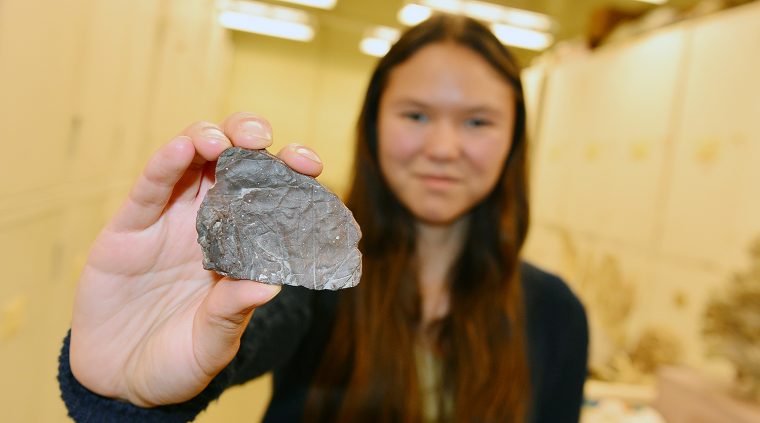

Sajirat Palakarn ’20 and earth and environmental science graduate student Melissa McKee ’17 work 40 hours a week on the project and have created a “fossil assembly line” in Exley Room 309. The students take turns sorting trays of fossils by class and phylum, and then match the fossils with identifying hand-written cards or books from an archaic card catalog, entering the information, piece by piece, into a spreadsheet. They’re expecting to itemize more than 15,000 fossils this summer.

“Look here,” Thomas says, while opening a wooden cabinet at random in Exley’s specimen storage room. “We’ve got shells, fossils of shells, one after another with no labels. They are all disorganized. Wouldn’t it be wonderful if we could make these accessible to the students?”

So far, the students have discovered dozens of fish fossils from the Jurassic Period (99.6 to 145.5 million years ago) and Triassic Period (251 million and 199 million years ago). They’ve encountered fossils of preserved leaves and insects from what is today Utah, Wyoming and Colorado, dating back to the Eocene Period, when the world was much warmer (40-45 million years ago). They’ve also found fossilized plants from coal deposits in Illinois (about 300 million years old), as well as fossil sea lilies (crinoids), which lived in shallow warm seas in what is now Indiana. Many of these fossils were collected by S. Ward Loper, who was curator of the Wesleyan Museum from 1894 to his death in 1910.

They’ve even discovered a plant fossil from Greenland, donated to the Wesleyan Museum in 1895 by A.N. Varse, who was on the second relief expedition attempting to assist Robert Peary on one of his early expeditions to explore Greenland and reach the North Pole.

“It’s really incredible to hold a piece of history like this in our hands,” McKee said. “Not only can fossils tell us what an organism might have looked like and how it lived, but fossils also give us clues about ancient environmental conditions. We can use fossils to understand how the Earth has changed over time.”

While most of the fossil finds are located in locked drawers in the hallways of Exley Science Center, the students also are cataloging fossils in the Joe Webb Peoples Fossil Collection, located on the fourth floor. The museum is named after the late Professor Joe Webb Peoples, who was chair of the Department of Geology from 1935 until his retirement in 1975.

The students not only catalog the artifacts, but they also write about their finds, and the museum, on a blog and on Twitter.

McKee and Palakarn, a College of Social Studies major, are constantly learning on the job. “I don’t have a science background, but here I am learning about unicellular microorganisms, sponges, coral, arthropods, trilobites and sea urchins,” Palakarn said.

“I know by the end of this summer you’re going to change your major to earth and environmental science,” McKee said. “I’m sure of it.”