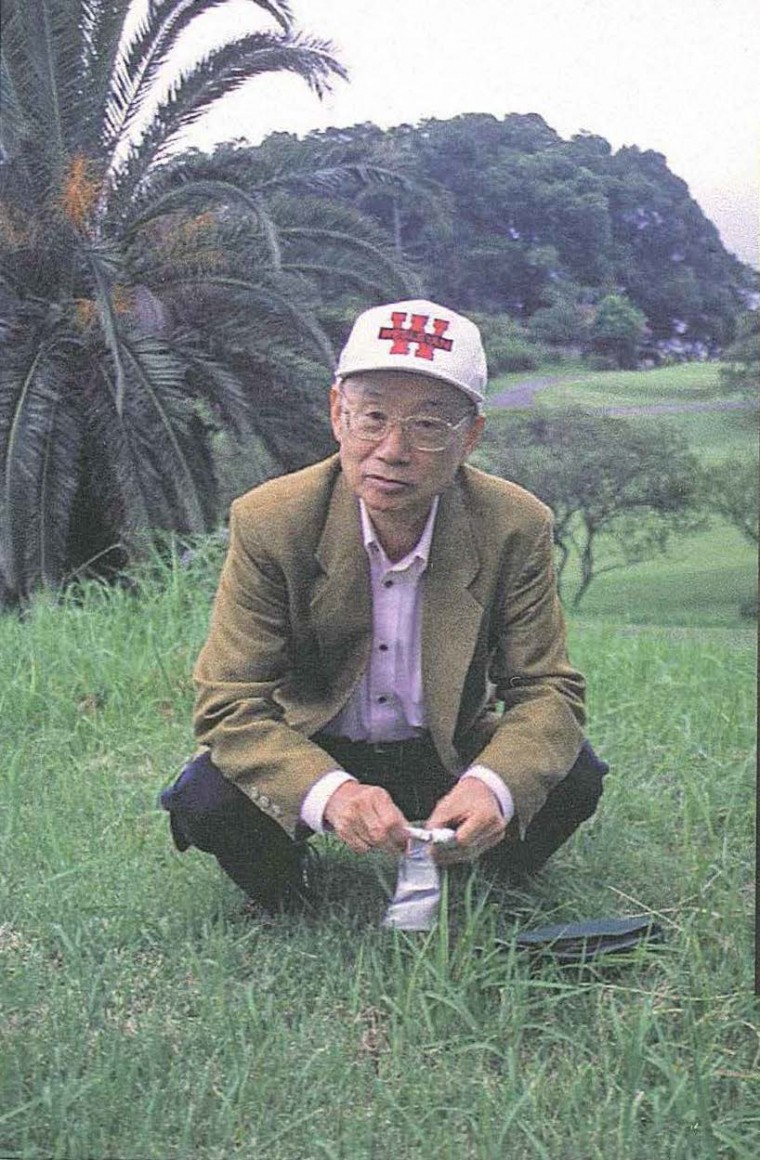

Nobel Prize Awarded to Satoshi Omura, Wesleyan’s Max Tishler Professor of Chemistry

Satoshi Omura was awarded the Nobel Prize for Medicine for developing a new drug, which has nearly eradicated river blindness and dramatically reduced mortality from other devastating diseases. Omura made the discovery that led to this drug while a visiting professor at Wesleyan in the early 1970s.

Omura has remained in touch with Wesleyan colleagues since then and in 2005 was appointed the first Max Tishler Professor of Chemistry, an honorary position. He returns to campus every few years to meet with faculty and present his current research.

The Nobel Committee honored Omura and William Campbell for discovering the drug Avermectin, as well as Youyou Tu, who discovered Artemisinin, on Oct. 5.

“These two discoveries have provided humankind with powerful new means to combat these debilitating diseases that affect hundreds of millions of people annually,” the committee said in a statement. “The consequences in terms of improved human health and reduced suffering are immeasurable.”

Omura came to Wesleyan in 1971 while on sabbatical from the Kitasato Institute in Tokyo, and worked closely with the late Professor of Chemistry Max Tishler for a year and a half. According to Albert Fry, the E.B. Nye Professor of Chemistry, who was a young professor here at the time, Omura brought to Wesleyan a number of extracts from soil samples to analyze their effects on harmful microorganisms.

“Within months after arriving here, he found a material (the microorganism Streptomyces avermitilis) that apparently was highly potent against a wide variety of bacteria, and quickly discovered that this was really a very attractive antibiotic,” Fry said.

Tishler, who joined Wesleyan’s faculty after retiring as senior vice president of research and development at the pharmaceutical company Merck & Co., introduced Omura to contacts at Merck, which developed the microorganism isolated by Omura into a powerful, broad spectrum antibiotic.

“This was one of the major discoveries that has happened at Wesleyan over the years,” Fry said. “So it as very exciting to see that develop from the initial discovery that Omura made into a product that has now saved many thousands of lives, particularly in Africa.”

The drug has also proven valuable in treating livestock and pets, as well as reducing in humans the incidence of filariasis, which causes the disfiguring swelling of the lymph system in the legs and lower body known as elephantiasis.

In 1994 Wesleyan awarded Omura an honorary Doctor of Science. In 2001, Omura established an endowed fund for the department, which supports operations, equipment and the work of junior faculty.

“We have been extremely fortunate to have Satoshi Omura as a member of this department. We are of course very excited and pleased that Satoshi has won this award,” Fry said. “In fact, some of us have thought that this was long overdue.”

Omura also has an ongoing relationship with faculty in the College of East Asian Studies, to which he donated cherry trees.

“I’m delighted that Dr. Omura has been honored for his research that began at Wesleyan–a truly important contribution to world health,” said Mary Alice Haddad, professor and chair of the College of East Asian Studies, professor of government, professor of environmental studies. “We look forward to deepening Wesleyan’s relationship with him in the future, possibly through the exchange of scientists.”

Hear a WNPR report on the Nobel Prize, featuring Fry, here. Japan’s Fuji TV also covered the news; Fry’s interview begins about a minute into the video.

In addition, Paul Modrich, who collaborated on DNA mismatch repair research with Manju Hingorani, professor of molecular biology and biochemistry, received a 2015 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. Hingorani, postdoctoral researcher Miho Sakato and Modrich co-authored a paper titled “MutL Traps MutS at a DNA Mismatch,” published in the July 21 issue of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

Modrich, along with Sweden’s Tomas Lindahl and Turkey’s Aziz Sancar “mapped and explained how the cell repairs its DNA and safeguards the genetic information,” the Nobel committee reported. Modrich’s research on DNA mismatch repair showed how cells correct errors when DNA is replicated during cell division.