Wesleyan Alumnus to Release PBS Documentary on Anti-War Protests

Director and Producer Stephen Talbot ’70 was an early adopter of the anti-Vietnam War movement. He first began to turn against the war as a member of the mandatory Junior ROTC at Harvard High School, now Harvard-Westlake, in California in the mid-1960s.

Talbot and his fellow high school classmates were given required trainings about the war. One of their JROTC instructors was called into active duty overseas in Vietnam and was severely injured. The news shook Talbot and he slowly began to question the war.

Now nearly 60 years later, Talbot has produced and directed a documentary on the anti-war movement and its impact on President Richard Nixon’s decision-making regarding nuclear weapons during the Vietnam War. The film, “The Movement and the ‘Madman,” premieres as a special presentation of American Experience on PBS on March 28 at 9 p.m. eastern.

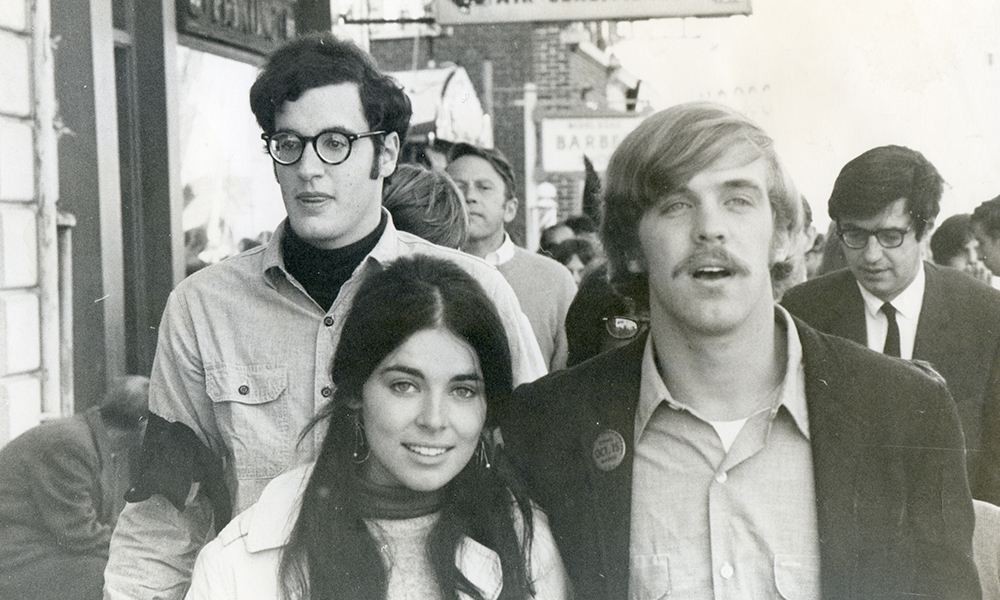

The film includes footage of anti-war protests in Washington D.C. in November 1969 that Talbot captured in his first documentary, which he filmed as his senior thesis at Wesleyan. It also includes a photograph of Talbot in downtown Middletown from October 1969, where he helped lead a local protest of about 1,500 people for the Moratorium to End the War in Vietnam.

“Once I started down that path, reading about the war, talking to people, watching documentary films, I pretty quickly became convinced that the war was a tragic war, that it was a mistake that it was not honorable, and that we should get out,” Talbot said. “Over the years I was at Wesleyan, I got more and more involved every year in activism against the war.”

After Talbot arrived at Wesleyan in the Fall of 1966, he soon realized he was among the most in-the-know students on campus about the situation in Vietnam. Politically active students at the time were zeroed in on the Civil Rights Movement, he said.

The focus of student activists began to shift toward the war starting in his sophomore year, he said. Then as the war continued to take the lives of Vietnamese people and American soldiers following the election of President Richard Nixon by a narrow margin in 1968, calls to leave Vietnam grew louder. In Talbot’s senior year, activists held the Moratorium to End the War in Vietnam, a nation-wide labor strike and anti-war demonstration attended by millions.

“We got the word of the Moratorium and we thought, ‘okay, let’s do something to go along with that,’” Talbot said. “And the big push there was to try to get off the campus and into the community, and to try to involve people in teachings and vigils, prayer groups, marches, rallies; (people) who normally who had not taken part yet in the anti-war movement, and to show how broad the anti-war movement was.”

Talbot and other members of the Union for Progressive Action, a group of student activists at Wesleyan who were against the war, recruited community leaders and professors to speak at the protest in October. President Edwin Etherington ’48 was one of several speakers that day, Talbot said.

Then Talbot and some friends rented a van and brought film equipment down to Washington D.C. for a few days in mid-November, 1969 for a second Moratorium protest. This protest included a symbolic “March Against Death,” where protestors wrote the names of soldiers killed or villages destroyed in Vietnam on placards hung around their necks and marched from Arlington Cemetery to the Capitol Building. Footage in the film from the “March Against Death” was captured by Talbot when he was still a student.

Protests continued until troops were recalled in 1973, but their true impact was not publicly known until decades later. Over the years former Nixon aides and involved decision-makers revealed aspects of Nixon’s “madman” strategy—he wanted to convince North Vietnamese leadership he was crazy enough to use nuclear weapons, as discussed in the documentary. As the war waged on, he realized this plan was untenable and the American public likely would not stand for it. “It’s mind blowing, honestly, we had no idea at the time,” Talbot said.

Talbot and his peers came away feeling that the demonstration itself had been very successful. “We were very pleased that we were part of it, but it was frustrating because the war didn’t end. We just, of course, had no idea what Nixon and Kissinger had been planning. So to discover it, and all these years later, is kind of stunning. And it’s why I decided to do this film.”