Barth’s Study Finds Mental Connections between Space and Time

“We’ve moved the meeting/truck forward.”

“That was a long wait/ hotdog.”

“We’re rapidly approaching the deadline/guardrail.”

English speakers use a shared vocabulary to talk about space and time. And though it’s not something we’re necessarily conscious of, psychologists have found that the identical words we use to describe our wait in line at the Department of Motor Vehicles and the length of an especially impressive hotdog are not a fluke, but rather are telling of the cognitive processes involved in thinking about time. Past studies have shown that priming people with spatial information actually influences their perceptions of time. For example, people primed to imagine themselves moving through space will make different judgments about the temporal order of events than people primed to imagine objects moving through space toward themselves.

Hilary Barth, associate professor of psychology, associate professor of neuroscience and behavior, is working to better understand the mental connections between space and time. She recently published an illuminating new study in the June 2012 issue of The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. According to Barth, it seems we use the more concrete world of space to think about the more abstract world of time.

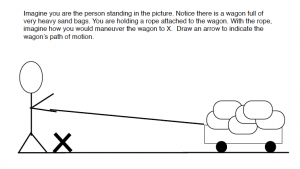

Barth and co-author Jessica Sullivan ’08—formerly one of Barth’s student in the Cognitive Development Labs, now a graduate student at the University of California-San Diego—noticed that though past studies in this area attribute the effects on participants’ temporal judgments to the spatial qualities of the prime used, most of the primes involved both space and movement. For example, previous studies have used primes that involve a stick figure walking toward a plant or pulling on a wagon—scenes that use motor words like “run” and show actors engaging in self-powered motion. Barth and Sullivan wondered whether this self-powered motion was a key component of the spatial primes, or rather was incidental. Their suspicion that the motor component played an important role was bolstered by the knowledge, from other past research, that hearing motor language activates the same areas of the brain as actual movement. That is, a person who imagines himself kicking will experience the same type of brain activation as if he kicked.

To try to separate out the effects of the spatial and the active motion components in the primes, Barth and Sullivan designed a study involving 198 participants drawn from the Wesleyan community. The participants—primarily students—were each assigned to one of six different test conditions. Participants were first given a very short “priming” story accompanied by a stick-figure drawing, and asked to imagine that they were the person in the story. (A separate group of people rated all of the stories to make sure that they were equally vivid and interesting.) Then they answered an ambiguous test question relating to time: “Next Wednesday’s meeting has been moved forward two days. What day is the meeting on now that it has been moved?”

In a control group, who did not get a priming story first, 77 percent of participants answered, “Friday.” When participants were first primed with a story about actively pulling a wagon towards themselves, they were significantly more likely to respond that the meeting had been moved to Monday. In contrast, participants who were primed with a story about a wagon rolling towards them on its own responded “Friday,” just like the control group. The results suggest that active spatial primes (which involve imagining a physical effort), influence our thinking about time more than passive spatial primes (which involve imagining motion without effort).

“We believe that these kinds of studies can help us understand just how it is that we think about abstract things we can’t see, feel, or touch, like time,” says Barth.