Formerly Enslaved Woman Honored at 1820 Gravesite

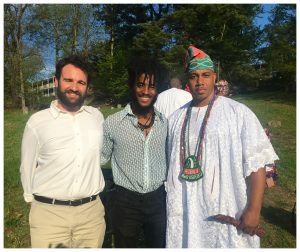

On May 9, a group of students, faculty, and Middletown friends joined Jumoke McDuffie-Thurmond ’19 and Chief Ayanda Clarke ’99 in a spiritual commemoration ceremony to honor a woman, Silva Storms, who died in 1820 and was buried in the cemetery on Vine Street, across from the Beman Triangle. Research indicates she had been born in Africa and was brought to Middletown as an enslaved person. The event was part of McDuffie-Thurmond’s research project for Black Middletown Lives, the service-learning course taught by Jesse Nasta ’07, visiting assistant professor of African American studies.

Nasta notes that McDuffie-Thurmond, who had been documenting the African American burials in the cemetery as part of his final project in the class, “completely took it upon himself to take that 10 steps beyond the assignment, to envision this ceremony. Jumoke is not just documenting the gravesites, but honoring the people who were enslaved here in Middletown.”

For his part, McDuffie-Thurmond remembers the first time Nasta took the class to the cemetery as a significant experience. “I’d never been to the section of the graveyard that was designated for Black Middletown residents, and Silva Storms’s gravesite—her tombstone stood almost alone in an open space—resonated with me. Professor Nasta told us it was the oldest tombstone in the African American section. I sat down there and listened to what was around me, what I felt, and I thought, I have to do something that tends to the spirit. We have a legacy of slavery in this land that constantly informs the space we live in—and it is unresolved. I wanted to do something that would resonate with those of us who live here now. It was a very intuitive decision.”

Hearing about McDuffie-Thurmond’s desire for a ceremony at the gravesite, Professor Liza McAlister put McDuffie-Thurmond in touch with her former student, Chief Ayanda Clarke ’99. As an undergraduate, Clarke had been part of McAlister’s course, Black Religions in the America. Clarke—an ethnomusicology major when he was at Wesleyan and a percussionist since he was five—has been a practitioner of the Orisa tradition all his life. He was nurtured by his parents, who are both esteemed initiates in the Orisa community. The practice and way of life had always been with him—and he has continued to grow in it.

“When I reached out to Chief Ayanda, he immediately understood what we were thinking of and rearranged his schedule,” says McAlister. “He arrived with four of his congregants, offered Yoruba prayers, and played Silva Storms’s name on the talking drum to remind the invisible world that she was not forgotten; that we remember her.”

Additionally, she notes, Clarke generously narrated the aspects of his service to the people gathered there who were not of the tradition: “He explained why we were there, and why she was there, and we should not lose hope, but instead use her life to move forward in the world,” says McAlister.

The ceremony also had a deeply personal significance for her. “I’m so proud that my student has become my elder. I have a low rank in the Orisa tradition—but Chief Ayanda outranks me. It’s a pleasure when a student continues on and becomes the one from whom I can learn.”

McDuffie-Thurmond was also pleased with his collaboration with Chief Ayanda. “It was a brilliant meeting,” he says. “Chief Ayanda is professional and insightful—and held space for everything we were thinking and feeling. I’m tremendously grateful for his generosity and that of the people he brought. This was a powerful way for an alumnus to contribute to the work of the University. I’ve been informed by his work, the way he tends to matters of the spirit. He gives context to the space we are moving in today.”

To further explain his work in the ceremony, Chief Ayanda talked about his work and the experience of returning to campus for McDuffie-Thurmond’s project in a Q&A. Chief Ayanda is an African American master percussionist, GRAMMY® Award–winning musician, arts educator, and lecturer in traditional African culture, music, and philosophy. He was installed as a chief in Osogbo, Yorubaland (Nigeria) and is a spiritual health counselor. He is also the founder and CEO of THE FADARA GROUP, LLC.

Q: Chief Ayanda, what was your reaction to this request from Jumoke McDuffie-Thurmond for your help in creating a ceremony at the gravesite?

A: I was very pleasantly surprised to hear that a Wesleyan undergraduate was aware of and interested in the care of the graves of these long-ignored ancestors, including that of Silva Storms. During my years at Wesleyan, we weren’t even aware of the significance of the Vine Street cemetery and certainly didn’t know the stories of those who were laid to rest there. Some time ago I read that years back a group of students respectfully reset fallen headstones on some of the graves in the African-American portion of the segregated cemetery. So now, Jumoke’s initiative provided a welcome opportunity to offer a ceremonial repositioning of positive energy and spirit. His work continues the legacy of progressive thinking and responsible action.

Q: How would you describe the nature of this ceremony?

A: The purpose and importance of the ceremony was to restore some reverence and honor to the souls who were laid to rest in that space. The graves had gone largely ignored for many years and the memories of those ancestors had been forgotten. But the name Silva Storms seems to keep jumping to the forefront, as if she is functioning as the matriarch of the cemetery, leading the call for attention. So, this ceremony specifically honored her spirit and her legacy. Yet as we uplift her memory, we shed light on all those interred in that cemetery.

When another progressive thinker like Jumoke emerges to continue the work of uncovering the life stories of those many still-nameless ancestors, we will gladly return to shed more light and share more love. This is far from the end. There is much more honoring and reverence work to do there.

Q: And how would you describe the outcome?

A: I was very happy with the collective positive energy that was shared at the Vine Street cemetery. The ceremony was beautifully powerful and effective because those who attended were purposeful and generous of spirit. There was truly honor and reverence in the hearts and minds of the students and faculty who participated. For that reason, our offering of prayer, drumming, light, and love affected everyone positively.

Now, the cemetery—intended to be a place for the present and the future to honor the past—fulfills its purpose as it should. Fittingly, the ancestors are remembered, can be learned from, and will be respected. And those who attended the ceremony had the opportunity, through their remembering and displays of respect, to walk away feeling uplifted and empowered.

The community-at-large is made better when we remember that since powerful ancestors existed, powerful people can walk the Earth, and a powerful future is possible. Hope and light is restored . . . as it should be.

For more information on the Black Middletown Lives service learning course, Professor Nasta and seven graduating seniors in the course will present their research as a WESeminar during Reunion/Commencement weekend, on Friday, May 25, 2018, from 3–4 p.m. in 116 Judd. See the complete listing of events here.