“You Just Have to Read This…” An Interview with Madam C.J. Walker Author Erica L. Ball ’93

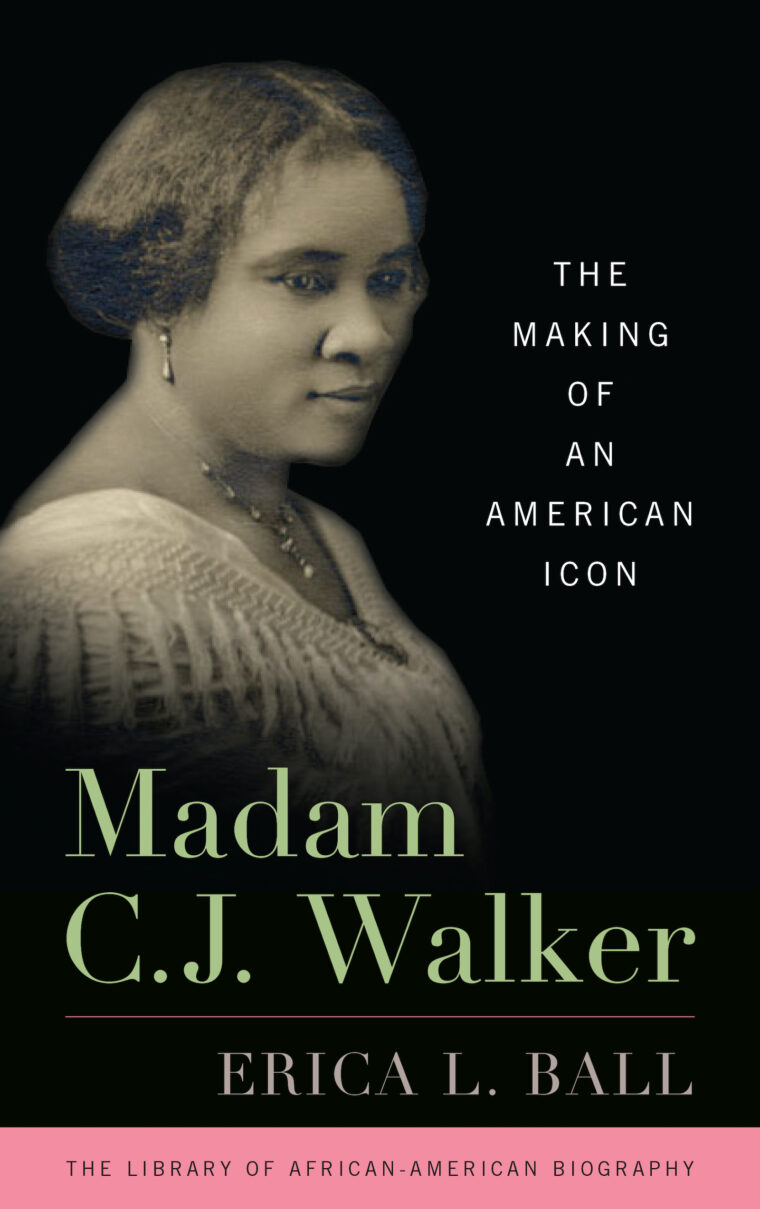

Erica L. Ball ’93 is a historian and the Mary Jane Hewitt Department Chair in Black Studies at Occidental College, who specializes in 19th and 20th-century African American history. Her second book, Madam C.J. Walker: The Making of an American Icon (Rowman & Littlefield, 2021), tells the life story of one of the most influential women in American history. Throughout the biography, Ball unravels Walker’s importance as a hair- and skin-care trailblazer, a philanthropist, and an activist.

Erica L. Ball ’93 is a historian and the Mary Jane Hewitt Department Chair in Black Studies at Occidental College, who specializes in 19th and 20th-century African American history. Her second book, Madam C.J. Walker: The Making of an American Icon (Rowman & Littlefield, 2021), tells the life story of one of the most influential women in American history. Throughout the biography, Ball unravels Walker’s importance as a hair- and skin-care trailblazer, a philanthropist, and an activist.

Annie Roach ’22, editorial student assistant, recently interviewed Ball about Walker and the process of writing the book.

Annie Roach ’22: What first inspired you to write this book? How did you first hear about Madam C.J. Walker?

Erica L. Ball ’93: Getting to the project was a circuitous route. A former professor from grad school was doing a series on famous American women, and she floated the idea of me potentially writing one on Madam C.J. Walker. That didn’t work out, but I’d already started the research and had gotten pretty far along down that road and knew I really wanted to continue working on the project. A friend put me in touch with the editors at Rowman & Littlefield, and that’s when the project really took off. That’s the short and technical answer to how this book came into being.

There’s actually a longer answer that stretches all the way back to Wesleyan, and to my history senior honors thesis project. Madam C.J. Walker actually makes an appearance in Chapter 3. There I talk a little bit about her work as a philanthropist and her prominent role the in purchase of the Frederick Douglass home. Weirdly, the roots of this book go all the way back to my senior year of college.

A.R.: What was the process of researching and writing like?

E.B.:I think of it as a three-stage process that actually took place simultaneously. One, the book is designed not just to introduce readers to Madam C.J. Walker the person; it’s also designed to serve as a lens onto the broader sweep of African American history. To do that, I had to make sure that I not only stayed current and up on all of the trends in African American history, but that I also allowed these historiographical trends to help me make sense of the larger political and cultural significance of Madam Walker’s life experiences.

The second aspect of the research process involved digging into the work that had already been written on Madam C.J. Walker, and of course, her great-great granddaughter, A’Lelia Bundles, has a wonderful cradle-to-grave biography of Madam Walker. Other folks have written great books on Madam Walker or published work analyzing the history of African Americans’ hair-care or beauty practices; all of that was very useful and helped to contextualize Madam Walker’s story.

The other critical aspect of the research process involved digging into the Madam C. J. Walker Manufacturing Company papers at the Indiana Historical Society. I found a wealth of material during my visits there.

A.R.: What did you find in your research that was most surprising?

E.B.: Two things, I would say. As I went through the papers held at the Indiana Historical Society, I was stunned by the number of requests for donations that she received. The files contain daily requests from random people all over the country, and outside of the United States, as well. Many requests come from well-known figures who are heads of institutions and presidents of HBCUs. And then there are other letters, like one from a fellow who was incarcerated at the infamous Angola Prison Farm in Louisiana. After hearing about Madam Walker, he writes a letter to tell her about his plight and to ask for help and a few dollars. Seeing that range of people reaching out to her was quite extraordinary. That ultimately led me to one of the key arguments I make in the book: Madam Walker was someone who fashioned herself into a modern celebrity—someone whom masses of individuals identified with, looked up to, and sought to reach out to—right at the moment when modern celebrity itself [was] being invented.

A.R.: In the context of our current world, what exactly makes this story so important and applicable now?

E.B.: Maybe it goes in two directions. On the one hand, I think of Madam Walker’s story as emblematic of a long freedom struggle. This is a person who insisted on not being limited by the terms that society set for her. She refused them. She didn’t believe them. And this was the starting point for her participation in the Black freedom struggle. This is a woman who moved, who would not be contained in one particular location, and who consistently defied Jim Crow limitations on Black freedom of movement. This is a woman who not only searched for opportunities for herself, but went on to create and expand opportunities for other people. Madam C.J. Walker was a person who refused to be satisfied with the political status quo for African Americans but engaged in a concerted, intense civil rights campaign—a multifaceted civil rights campaign—to fight for better conditions for people of African descent. I think she represents the capacious nature of the African American freedom struggle. And I think that can be a useful lesson for us today. It’s a long journey, a long struggle, one that can take many forms and requires different types of actions.

There might also be another lesson in there for folks who are well-positioned, like wealthy celebrities. Madam Walker’s life story raises some questions for them: What do you do with your money? What do you do with your fame? Is it just for you, or do you do what someone like Madam C.J. Walker did, and insist on using it for the public good?

A.R.: What is the most important takeaway that you hope readers will get out of reading about Madam C.J. Walker?

E.B.: She was more than a lady who was just interested in something that people often think of as frivolous (beauty culture) and she was not focused on helping Black women imitate white standards of beauty. She spoke in terms of health, she spoke in terms of agency, and she advocated for the independence of Black women. She was much more than some of the caricatures that emerged in the ’60s and ’70s made her seem. That’s why her memory was so important to African Americans for much of the 20th century.

A.R.: What was your time at Wesleyan like?

E.B.: I grew up in a military family and went to high school in Arizona, where my father was stationed at the time. I’d never been to Connecticut. It was a big change for me. I spent a lot of time hanging out at WesWings, I was a member of the Cardinal Sinners a capella group, and I sang in a blues band called Johnny Vess and the Westones. I had a great time and I learned so much; Wesleyan was a formative experience for me.

Sometimes I think if I hadn’t gone to Wesleyan, my life would have been very different. There were paths that I didn’t know were possible for me to take. One was becoming a researcher, a scholar, a professor. As I worked on my honors thesis, I got it into my head that this is something I might want to keep doing with my life. I also made some great friends. I actually live fairly close to one of my Foss 9 dormmates from frosh year. It’s a small world.

A.R.: Anything else you want to add about your book or about Wesleyan?

E.B.: Wesleyan taught me how to think differently, how to think broadly, how to wrestle with new ideas, how to be open in ways that I didn’t know that I could be. It’s an extraordinary institution that develops habits of mind that are conducive to better world-making. It opens people up in ways that are extraordinary and profound. And I will always be grateful for having had the opportunity to attend Wesleyan.