Scientific Images of Nanoparticles, Colliding Stars, Learned Words Win Annual Contest

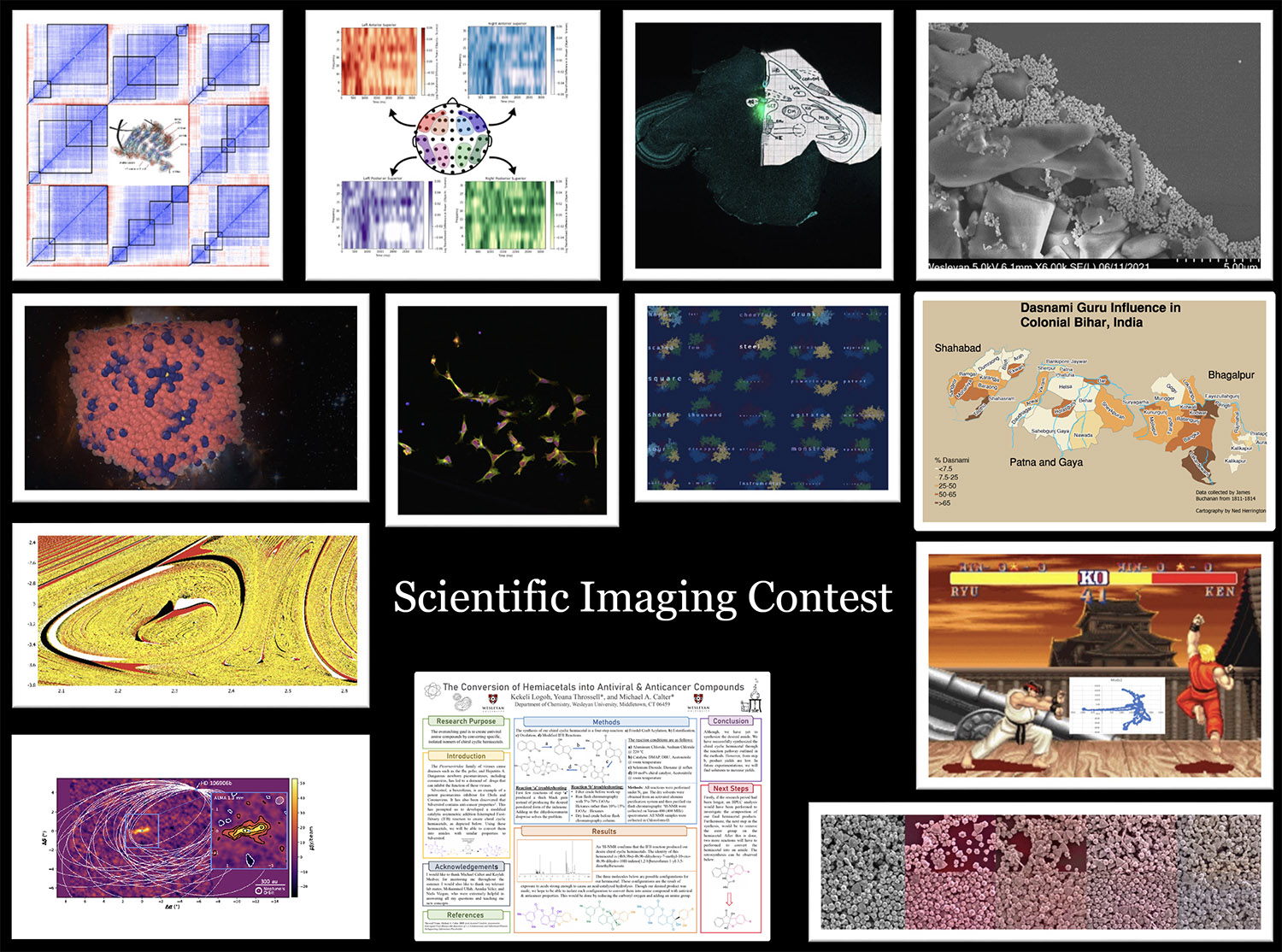

At first glance, a viewer sees a single image of pink-tinted cubes, resembling a bacteria culture from high school biology.

But upon closer examination, the viewer begins to see a series of other shapes—triangles to hexahedrons to tetahexahedraons (cubes with four-sided pyramids on each face).

“If you stare at this image for a while, you can see that it’s actually a series of five images in the top row, and five images on the bottom row, and each of these images show us nanoparticles that are made of gold and copper,” said Brian Northrop, professor of chemistry. “It’s intriguing, captivating, and visually very interesting.”

The image, which depicts bimetallic gold-copper (Au-Cu) nanoparticles synthesized with varying concentrations and amounts of sodium iodide, was created by Jessica Luu ’24 using a scanning electron microscope. It also was the first place winner in Wesleyan’s 2021 Scientific Imaging Contest.

The annual contest, spearheaded by Wesleyan’s College of Integrative Sciences, encourages students to submit images and descriptions of the research that they’ve been conducting over the summer.

The judges this year included Northrop; Amy MacQueen, associate professor of molecular biology and biochemistry; and Renee Sher, assistant professor of physics. The top three submissions win cash prizes.

“What makes the winners stand out are (1) the images are intriguing and we want to find out more, (2) the paragraph they provide allow a broad audience to learn about the science behind their work, and (3) after reading the text we feel their description elevates the art even more,” Sher said.

Luu explained that as she increased the amount of sodium oxide with both copper and gold, the metals’ nanoparticles changed in terms of shape, sharpness, and even color. Since these results are called “gradients,” Luu decided to use an actual gradient of colors using Photoshop to represent the changing conditions.

“We found it really visually intriguing and you could really see all of the science that goes into creating these nanoparticles,” Northrop said.

Luu, a chemistry and “tentatively” environmental studies major, created the nanoparticle images this summer while working in the lab of Michelle Personick, associate professor of chemistry. Luu is expanding on gold-copper nanoparticle research first synthesized by one of the group’s alumni, David Solti ’18.

“I decided to enter the contest because this was a great opportunity to combine art with science,” Luu said. “If I wasn’t a science major, then I would most likely be studying art. I hadn’t previously done any artwork that was based on research, so I thought this could be an interesting way to test the waters and see what I could create. Since nanoparticles are geometric, I have also been using modular origami to understand their structures—though with limited success currently … Perhaps I will have enough of an understanding to create models to represent the particles I’ve been working with in the future!”

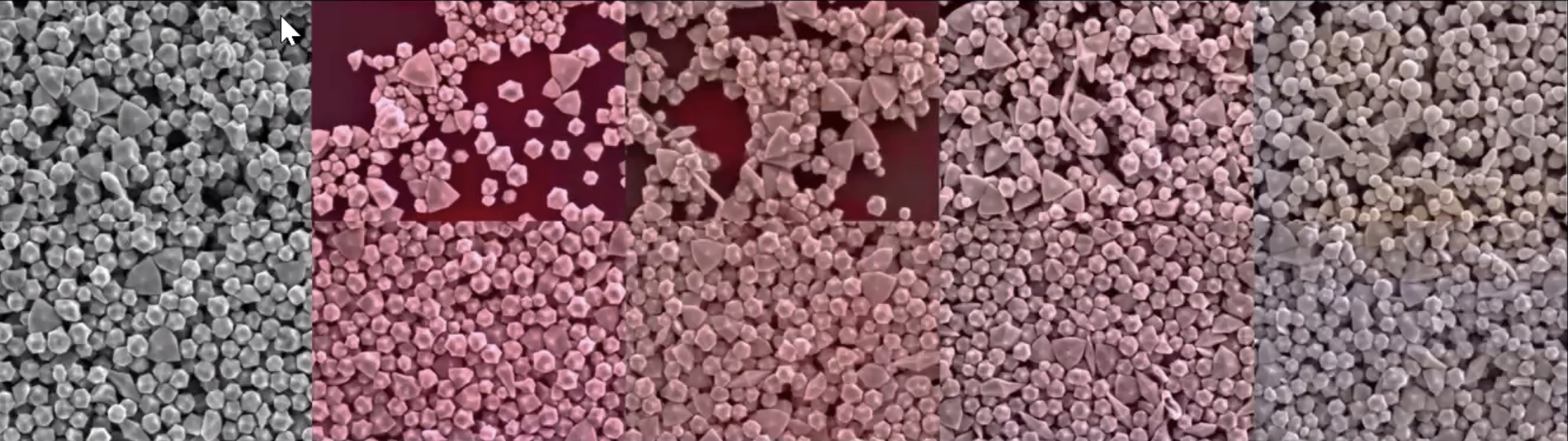

Morgan Long ’22 took second place with his diagram interpreting an integration of more than 30 million different initial conditions for a bound pair of orbiting stars colliding with another incoming star.

The yellow pixel represents an unknown outcome, while the others correspond to a different one of the three stars escaping. The points where white, black, and red all touch are locations where three stars all get close to each other, and all three might even collide head-on.

“One of the things that really jumped out at us is that the yellow pixels represent an unknown outcome— a renewal—a wait for the unknown, really unknown,” Sher said. “It’s so totally artsy, and fascinating.”

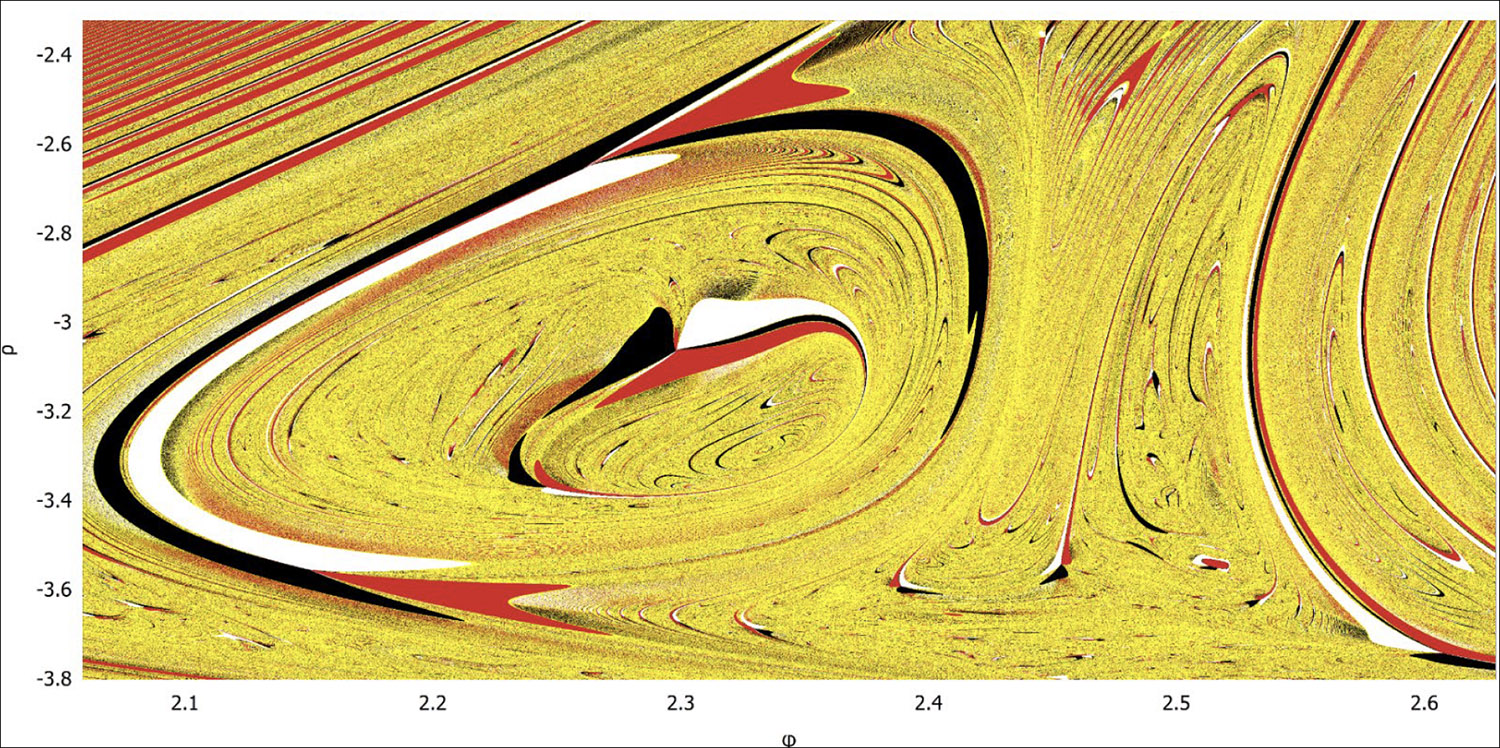

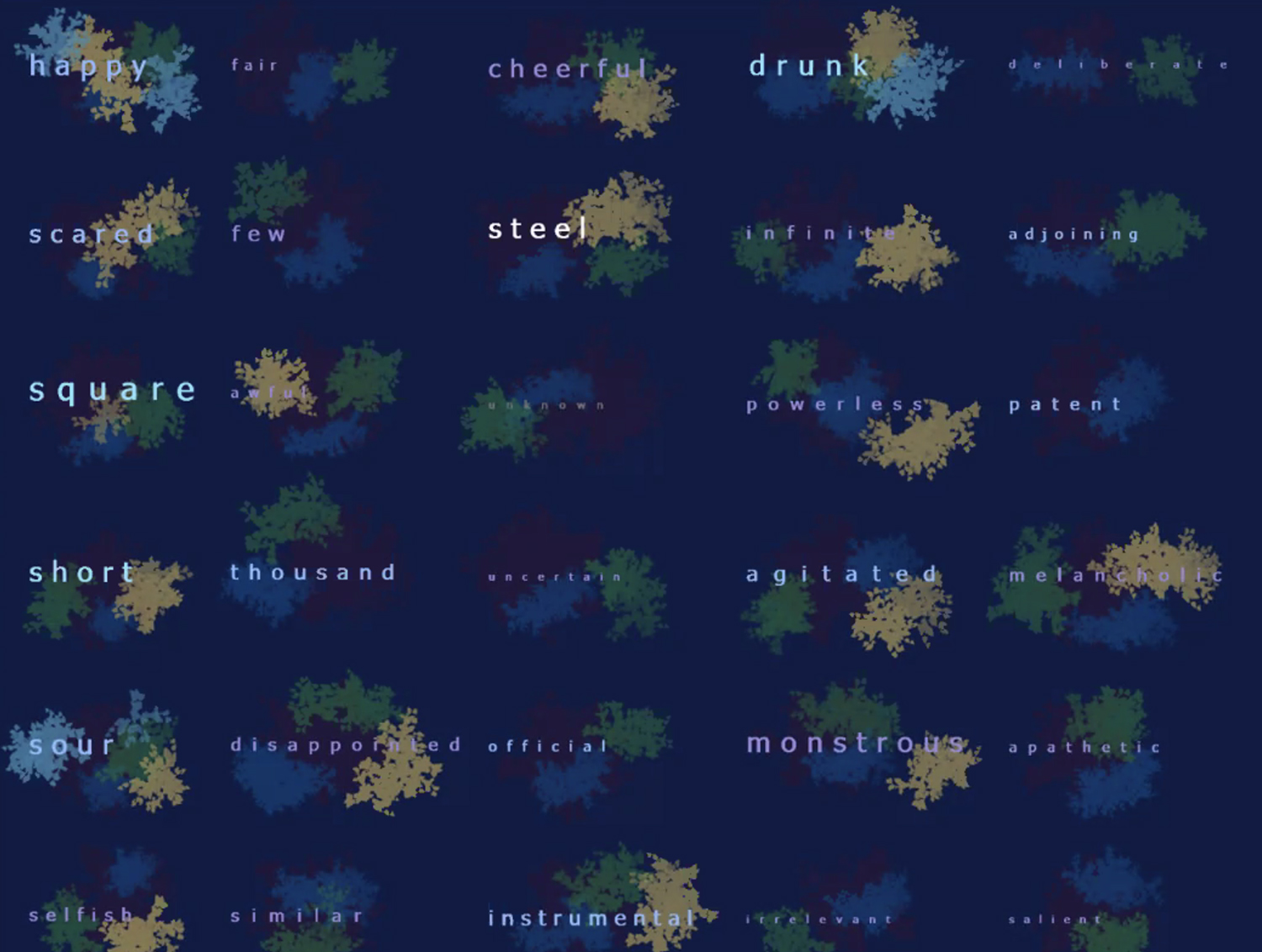

Wiralpach Nawabutsitthirat ’22 took third place with this image representing how different variables affect our ability to read words. Thirty words are displayed in columns, in the order in which people tend to learn words in life. The word learned at the youngest age (i.e., happy in this study) is located at the top left, while the word learned at the oldest age (i.e., salient in this study) is at the bottom right.

“Words with more definite meanings are processed quicker, just as words with more contrast from the background are easier to read. Taken together, words with more striking visuals are words that are easier to read and understand,” Nawabutsitthirat explained.

MacQueen admired Nawabutsitthirat’s submission for not only being aesthetically appealing but for representing how eye-catching units of human language can be.

“Wiralpach’s image— it jumped out to all of us,” she said. “There’s shapes and colors and sizes of things to look at, but maybe because of our intimate connection with the written word as humans, this work also engaged our curiosity, so we were spurred to ask, ‘Why do you know these words? What do the different sizes mean? What does the spacing between the letters mean?”

The judges also credited Nawabutsitthirat’s accompanying legend that helped inform and transform the way they thought about the piece.

“Certain words can elicit a greater sensory experience than others, and so the entry was notable for initially capturing our curiosity, making us question things,” MacQueen said. “After reading the descriptions, we were feeling more informed and had a deeper connection with the art.

Northrup applauds all thirteen students who submitted images this year.

“Our goal is to promote and represent science for not only the scientifically literate but for a general audience,” Northrop said. “This year we had many captivating images that drew us in.”